Have you heard of that new factory in Shenzhen, China that manufactures perfect products 100 percent of the time with zero defects?

Have you heard of that new factory in Shenzhen, China that manufactures perfect products 100 percent of the time with zero defects?

Neither have I.

Unfortunately, no factory churns out perfect products all the time—not in the aerospace industry, not in the automotive industry and certainly not in the consumer products industry.

Product defects are common in manufacturing. They can come in different forms, sizes and severities. And they’re a problem that can significantly affect you, as an importer, and your bottom line.

So how can you handle defective products?

Managing defects starts with setting expectations during the sourcing process and continues throughout production to the time when your supplier ships the finished goods.

Reaching the level of quality you and your customers expect can mean a long road ahead. But a systematic approach can get you there. And it starts with choosing the right suppliers.

Set clear expectations when choosing suppliers

Have you ever heard the expression, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”?

There’s perhaps no better example of this than when it comes to preventing defective goods in the manufacturing process.

Taking some time to properly document your requirements will go a long way in helping you choose the best supplier later. Reviewing these expectations with suppliers also helps you avoid needing costly corrective actions later.

Product requirements

You should have some idea of your product requirements well before choosing a supplier. And the clearer you can be in conveying these to your supplier, the less likely you’ll be to receive defective or unsellable goods.

Many importers choose from suppliers’ catalogs of “white label” products to simply import with their own branding. But if you’re importing a new product you’ve designed, the manufacturer will probably need you to provide detailed specs with design drawings.

Product defect tolerances

Consider the value of your product. Let’s say you’re importing those plastic-beaded necklaces that are handed out for free at the Mardi Gras festival. Are you going to reject an entire order just because there are small scratches in the paint on 20 percent of the beads? Probably not.

Now let’s say you’re importing sterling silver bangles that retail for $80-$150 each. You’ll probably be VERY sensitive to any scratches on the surface of the product because your customers will be.

These considerations will help you classify different types of quality defects in your product (related: 3 Types of Quality Defects in Different Products). And classifying defects prepares your supplier so they can take steps to avoid the types of issues that will lead to rejections.

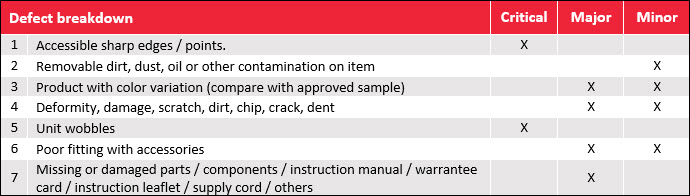

The best way to classify defects early is to create a detailed QC checklist showing a breakdown of possible product defects and how they should be classified (e.g. “minor”, “major” and “critical”). It’s also helpful to include photos, if possible, to distinguish between defects that vary in type and severity.

Once you’ve appropriately sorted the different types of defects into your checklist, it’s time to quantify your tolerance for each. This is often expressed in terms of acceptable quality limits, or acceptable quality levels (AQL).

Once you’ve appropriately sorted the different types of defects into your checklist, it’s time to quantify your tolerance for each. This is often expressed in terms of acceptable quality limits, or acceptable quality levels (AQL).

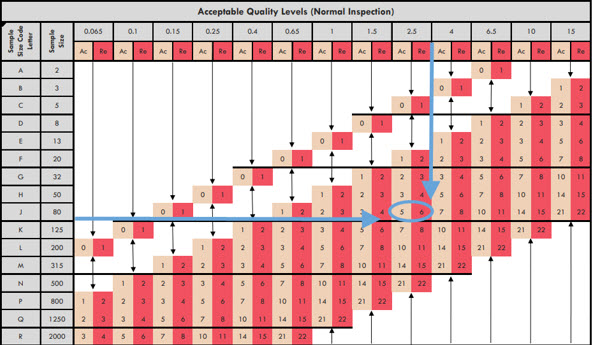

Quality control practices typically rely on acceptance sampling to determine whether to accept or reject a shipment based on a sample of goods pulled from the total lot. AQL establishes the maximum acceptable number of product defects found in a given sample based on defect classification.

Let’s say you consider a scratch on your product to be a “major” defect, and you’ve set your AQL for major defects as 2.5. This means the maximum number of scratches or other major defects allowed in a random sample of 80 pieces is five. And you’ll reject the order if QC personnel find six or more major defects in the sample.

If differences in the dimensions of your product will affect salability, include a sizing chart or table with relevant measurement tolerances. This is especially relevant for hand-sewn products like footwear and garments that are more susceptible to human error.

If differences in the dimensions of your product will affect salability, include a sizing chart or table with relevant measurement tolerances. This is especially relevant for hand-sewn products like footwear and garments that are more susceptible to human error.

Define penalties for excessive quality defects

Most financial penalties we see from importers are chargebacks for re-inspection. The importer sends a professional third-party inspector to the factory to check the goods before shipping. The goods end up failing inspection due to unacceptable quality problems. And the importer asks for corrective action followed by a re-inspection, which they ask the supplier to pay for.

Some importers will also ask their supplier for a partial or full refund for a PO if a significant portion of the goods they receive are unsellable. Besides limiting the cost to the importer for what they see as supplier negligence, chargebacks can also incentivize quality improvement.

Penalties like these can work well for some importers and not others. They tend to be much harder to enforce when:

- The importer that’s introduced the penalty is a relatively small buyer with little or no leverage to influence their supplier; or

- The importer has introduced the penalty in response to problems, as opposed to setting the expectation upfront

It’s not unusual for importers to hold their suppliers financially accountable for meeting a certain quality standard. But the best time to start is early in the sourcing process when you’re still considering which suppliers to work with.

Explain this with your other expectations upfront. And when you’re ready to place your first order with a supplier, include this point directly in the PO. Depending on where your supplier is based, it may still be hard to legally enforce the penalty. But at least your supplier can’t argue later that they didn’t know about it.

Verify new manufacturers or vendors

Contacting multiple suppliers and discussing your expectations with them should leave you with a shortlist of potentials to work with. These will be suppliers you think can provide the goods you need at a reasonable price while meeting your quality and delivery expectations.

Contacting multiple suppliers and discussing your expectations with them should leave you with a shortlist of potentials to work with. These will be suppliers you think can provide the goods you need at a reasonable price while meeting your quality and delivery expectations.

The problem with this list is that most of the information it’s based on has come from the suppliers themselves—it’s unverified.

That’s why the next steps to properly vetting your potential suppliers are to investigate the supplier on site and review products they claim they can deliver.

Screen suppliers by evaluating their facilities

There’s no better way to get a sense of a supplier’s capabilities than by seeing them at work firsthand.

Many importers opt to travel directly to their supplier’s facility and meet with them there. Meeting with potential suppliers in person comes with some clear benefits:

- If you know what to look for, you can gather plenty of information during your visit that will help you qualify the potential supplier.

- You get the opportunity to build a close relationship with your supplier from the onset.

- You can review your requirements with the relevant people in detail to ensure everyone’s on the same page.

Note: you may want to bring an interpreter if you can’t speak the local language. Salespeople from a vendor usually speak English well, but production managers at factories often don’t.

- And if you time your meetings wisely, you can meet with most or all of the suppliers on your shortlist in the same trip.

Despite these advantages, visiting suppliers in person to evaluate them isn’t for everyone. Depending on your experience and the number and location of the suppliers you plan to visit, doing so can be costly and ineffective.

That’s where hiring a local professional can be a preferred alternative.

Supplier qualification audits

Some importers are more comfortable hiring a professional  auditor to investigate their potential suppliers. Others may feel competent doing the auditing but find it too costly to travel halfway across the globe just to visit one or two factories.

auditor to investigate their potential suppliers. Others may feel competent doing the auditing but find it too costly to travel halfway across the globe just to visit one or two factories.

These importers often choose to send a trusted third party to audit the potential supplier for them. This person could be a friend who’s based near the facility. Or it could be a professional, local auditing firm that specializes in more formal audits.

There are several common types of factory audits available. But the most popular for screening a potential manufacturer is a supplier qualification audit. Sometimes called a quality systems audit or a supplier evaluation, this type of audit typically probes several areas of a factory, including:

- Production capacity

- Internal quality control systems

- Any on-site lab testing capabilities

- Machine and equipment maintenance

- Materials and finished goods storage

- Relevant documentation, e.g. business registration, export license, etc.

- Recruitment and training practices

This kind of audit report gives you a “snapshot” of the facility. It not only shows you how likely a supplier is to manufacture defective products, but also what systems they have (or lack) to catch and address quality problems before shipping.

Regardless of whether you visit potential suppliers yourself or send someone on your behalf, evaluating their facility is an essential step in the screening process.

Review product samples to further establish quality standards

You can learn a lot by evaluating a supplier’s facility. Building a detailed QC checklist and reviewing it with a prospective supplier is good too. Getter their buy in and assurance that they understand and can meet your requirements is even better.

But nothing beats being able to actually hold the resulting product in your hands to see for yourself.

Most suppliers will be happy to send you product samples for review, provided you cover their production and shipping costs.

But keep in mind that it’s not uncommon to need multiple revisions of product samples before you arrive at a “golden” sample that sufficiently meets your standards. You could spend valuable weeks sending samples back and forth for review. Testing samples in a laboratory can drag this out further.

As with auditing a supplier, some importers will hire a local professional to review product samples for them. QC firms can often receive your samples in less time than shipping overseas. They’ll check the samples against your specifications and any QC checklist and issue you a report with photos and findings.

Once you’re confident in the sample you’ve received, it can serve as a model for reference during production in the factory.

Identify and address defective products with inspection

A great way to manage defective products is to catch quality issues early before they make their way into the finished goods. Identifying issues before shipping helps you avoid assumptions about product quality—assumptions that can cost you money if you find a significant portion of the order you receive is unsellable.

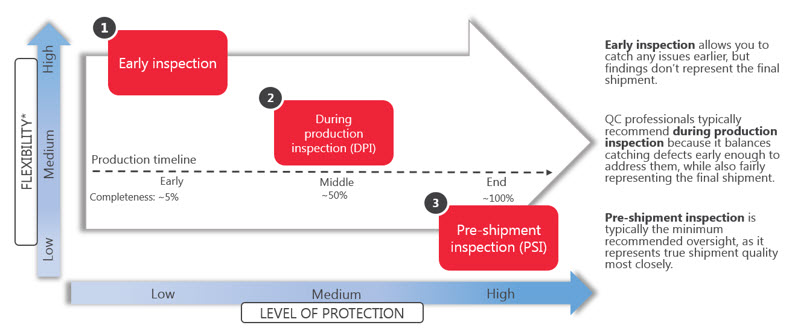

There are different stages during the production process where inspection can be performed to show you the current state of your order. And just as with auditing the factory and reviewing samples, you may choose to do inspections on your own or hire an independent third party.

Raw material inspection

Part of what’s often called incoming quality control, inspecting raw materials and components before production begins can reveal costly quality issues.

For example, let’s say you’re manufacturing leather bags and want to hold your supplier to a certain standard when it comes to choosing a quality leather hide for production. One of the best ways to do this is by actually checking the incoming raw materials in the warehouse before the factory starts working.

Without this added oversight, you might discover months later that workers used inferior materials, leaving you to either:

later that workers used inferior materials, leaving you to either:

- Accept the bags as they are, even though they don’t meet the expectations of you and your customers, or

- Start over by manufacturing an entirely new order of the same bags (and possibly finding a new supplier for the order)

Save yourself the nightmare of frantic backpedaling by catching any quality issues related to raw materials and components early.

DUPRO inspection

A during production (DUPRO) inspection can help you find issues appearing in an order while production is underway. You or your inspector can pull samples of the product from different stages in production to identify any issues occurring during specific processes.

DUPRO inspection is especially helpful if you’re dealing with:

- Shipments of large quantities of goods with ongoing production

- Products with numerous production stages; and

- Products susceptible to defects and other issues that can’t be reworked or fixed later

Wood molding is typically manufactured in larger quantities with a lengthy production timeline. A professional SLR camera involves many different production processes and components. And many of the defects that might occur during production of a plastic, injection-molded display case cannot be reworked.

All of these are examples of products where a DUPRO inspection is ideal for helping you address any defect causes earlier.

Pre-shipment inspection

Pre-shipment inspection, or final inspection, occurs near the end of production, typically when 80 -100 percent of an order of goods is finished and packaged. For many importers, pre-shipment inspection is the bare minimum quality oversight they want for an order.

Like inspection at other stages, pre-shipment inspection typically involves pulling a random sample of goods and looking for quality defects, non-conformities and other issues.

The advantage pre-shipment has over earlier inspection is that it offers insight into the way the goods will actually leave the factory, including verifying packaging. This gives you a high level or protection but at the cost of limited flexibility. That’s because inspection at an earlier phase gives you more time to address any defects or other issues found.

Plan for any defects that remain in finished goods

Plan for any defects that remain in finished goods

Despite importers’ best efforts to catch and address defects early, some quality issues almost always remain in the finished goods. You may find defects are minor enough and in limited-enough quantities for you and your customers to accept.

Other times, you may not be able to tolerate the issues found. You’ll need to decide what to do in such cases to resolve the issues with the current order, if possible. And if not possible, you’ll want to take steps to prevent the same problems in future orders.

Account for defective products with extra inventory

Sometimes you can anticipate a certain percentage of the finished goods you buy will be defective or otherwise unsellable. And depending on your relationship with that supplier, you might ask them to ship extra units, such as five percent of the total order quantity, to account for this.

This strategy is more popular among importers of lower-value products like plastic containers for food storage or earbuds. This can be a less time-consuming safeguard in lieu of asking the factory to rework or repair defective products before shipping.

But remember, you’re still paying for those extra units. The defective units the supplier has sent replacements for are waste. And your supplier is absolutely raising their per-unit price to compensate for that.

Moreover, ordering extra inventory to compensate for defective goods is not an ideal or long-term solution. You eat the unnecessary extra cost, and your supplier does nothing to improve.

Rework defective products

Product rework may be an option if the defects you find are the sort that can be remedied at the factory. But keep in mind that rework means additional handling, which can add more defects than it helps remove.

Product rework may be an option if the defects you find are the sort that can be remedied at the factory. But keep in mind that rework means additional handling, which can add more defects than it helps remove.

One such example is flash, excess material commonly found on molded products. Reworking this defect often requires a worker to take a knife to the product and manually cut away the excess material. This may be effective at removing the flash but could also cause scratches or other damage in the process.

Another factor you should consider before requesting rework is time. How far away from meeting your shipping deadline is the supplier? When are your customers expecting to receive the goods? If you desperately need to ship the order, it may not be worth reworking defective products at the expense of delaying shipping.

Asking the manufacturer to rework defective products before shipping is one way to hold them accountable and address any quality issues. But always consider the value of the PO, meeting deadlines and the potential consequences of double handling.

Destroy defective goods that can’t be fixed

You may have a large quantity of branded, defective products you cannot rework, sell or salvage. You don’t want to ship the goods. But you can’t just tell your supplier to discard them, either.

What if your supplier turns around and sells your unwanted goods on the grey market? Now your brand is out there on a bad product. And if the product has safety issues, you now have a potential legal liability on your hands.

Though it may seem counterintuitive, resorting to total product destruction is often the best, if only, solution. Only by witnessing the complete destruction the goods beyond the point of salvaging them can you be sure those goods won’t come back to haunt you in some way or other.

Discuss the problem with your supplier. Determine the most practical and cost-effective method of destruction. And verify by either personally watching the destruction process on site or sending a trusted third party to observe and report back to you.

Conclusion

Try as we might to achieve a perfect product, defects are a fact of life—an unavoidable consequence of combining great ideas with materials to manufacture the products we love.

Whether they’re minor defects, major issues or critical to consumers’ safety, directly and openly managing any problems with your supplier is crucial. Knowing how to handle defective products can save you time, money and your reputation as a brand.

Remember the words of the late Vince Lombardi, famed coach of the Green Bay Packers: “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence.”

Editor’s note: This post was originally published in August 2016 and has been updated for freshness, accuracy, and comprehensiveness.

How do you manage defective products? Share your experiences in the comment section below!