Some products should never see the light of day

On September 6, 1980, an Iowa woman named Patricia Kehm died of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) linked to a product that would be pulled from shelves only days later. Kehm’s family went on to sue the manufacturer, Procter & Gamble, and were awarded $300,000 by a federal court in what was then the first successful wrongful death suit brought against the company.

The product in question? An innovative, new tampon sold under P&G’s subsidiary brand Rely. The Rely tampon was made of synthetic materials which, while superabsorbent, also provided an ideal environment for the growth of harmful bacteria that causes TSS. The link between the product and TSS led to more than 400 other civil suits, prompted P&G to allocate $75 million to Rely-related litigation and likely cost the company millions of dollars more in recalled goods.

The product in question? An innovative, new tampon sold under P&G’s subsidiary brand Rely. The Rely tampon was made of synthetic materials which, while superabsorbent, also provided an ideal environment for the growth of harmful bacteria that causes TSS. The link between the product and TSS led to more than 400 other civil suits, prompted P&G to allocate $75 million to Rely-related litigation and likely cost the company millions of dollars more in recalled goods.

What’s especially troubling in the Rely case is that the product predated Food & Drug Administration (FDA) regulations that would have reclassified tampons as medical devices. So at that time the company wasn’t bound by federal law requiring clinical testing that may have caught these health risks before the product reached market.

The Rely tampon represents just one product in a sea of countless others that never should have reached market. Though the recalled goods were most likely incinerated or otherwise destroyed, product destruction came too late for Patricia Kehm and others who suffered from unforeseen side effects of the product.

As an importer, total product destruction is a solution you probably hope never to have to use when faced with quality issues or safety concerns with your products. But as we’ve seen from the Rely example, preemptive destruction of defective or unsafe goods not only protects your brand’s reputation and prevents litigation. It can also save lives.

Total product destruction as a preemptive measure

You may very well find yourself in a situation where your goods are unsellable and certified destruction and product disposal is the best way forward.

So what are these situations that may call for destruction and what are the best methods for ensuring goods are destroyed properly? By the end of this eBook, you’ll be prepared to answer these and other relevant questions as they relate to you and your particular products.

Read along, email a PDF to yourself for later by filling out the form on the right or click the links above to jump to the section that interests you most!

Chapter 1: Why Resort to Total Product Destruction

If ordering the wholesale destruction of goods you’ve just paid a supplier to manufacture sounds at all wasteful, that’s because it is. Product destruction is often a major setback for importers that deem it necessary. Not only are they discarding mass amounts of inventory, but they’re also likely undoing months of preparation, from evaluating suppliers and sourcing parts and materials to finding distributors and promoting the product.

What would prompt an importer to resort to product destruction and disposal? The most common reason is that the goods are seriously defective or substandard to the point of being unsellable. There may be issues with your product so severe:

- Your customers will return your products

- Your products will pose a safety risk to end users; or

- Sale of your product will otherwise damage your brand

Simply withholding any shipments of goods with these types of issues from your distributors may seem adequate to keep them out of the hands of consumers. But this does little to help keep your defective products off the grey market.

What is the grey market?

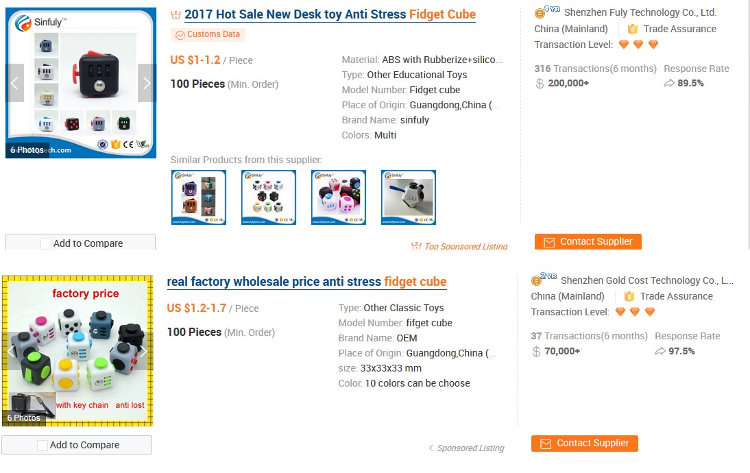

You might be familiar with the black market, whereby goods are bought and sold illegally. Unlike the black market, the grey market is composed of distribution channels that are legal but unintended and unauthorized by the manufacturer. For you as an importer, this often means the rejected products you've asked your supplier not to ship have been sold “out the back door” either locally or exported.  This seems to be what happened to Antsy Labs’ widely popular Fidget Cube.

This seems to be what happened to Antsy Labs’ widely popular Fidget Cube.

A lesson from the Fidget Cube

The Fidget Cube is one of the highest-funded products featured on Kickstarter, in the crowdfunding website’s history. The creators, a company called Antsy Labs, successfully raised nearly $6.5 million in pledges for the product in 2016, easily surpassing their goal of $15,000. As the crowdfunding campaign progressed, major news outlets quickly picked up the story. And as Christmas drew near, anticipation for the product boiled to a fever pitch.

Then the company suddenly released this statement: “We need to let you know that we discovered an issue that we had to make a tough call on… We had to make the difficult decision to briefly pause shipping in the name of quality.”

Antsy Labs had discovered a quality defect in their product that they considered serious enough to delay shipping the order until the issue could be fixed. But what started as a minor hiccup in production soon ballooned into a much bigger problem when dozens of Fidget Cube listings began appearing on ecommerce sites, including eBay, Amazon and Alibaba.

What some later speculated—and what very likely may have happened—is that the factory producing the official Fidget Cubes saw an opportunity to turn Antsy Labs’ problem into their own profit by selling the substandard goods on the grey market. While Antsy Labs didn’t want to enter market with a faulty product, plenty of distributors were happy to do so. The consequences for Antsy Labs were swift and serious:

- Other online sellers quickly capitalized on the company’s delay and began selling their own versions of the product (there was a patent pending for the Fidget Cube at the time, but no patent had yet been issued). One seller sprung at the opportunity to manufacture a copycat product, the Stress Cube, beating the Fidget Cube to market and earning $345,000 in just two months.

- The company’s brand reputation waned as consumers bought substandard products mimicking their design—and likely Antsy Labs’ own defective inventory on the grey market—that didn’t live up to quality standards the company touted.

So while legitimate goods can be legally traded on the grey market, despite the manufacturer’s intent to control distribution, serious problems with intellectual property and brand image can result for the manufacturer. Worse still, products with safety concerns sold on the grey market can be hazardous to consumers and expose the manufacturer to liability, despite the manufacturers’ intent to withhold such products from market.

How do products end up on the grey market?

Now that we’ve seen some of the potential consequences of your goods ending up on the grey market, let’s explore some the ways your goods could appear there in the first place:

- Suppliers sell unwanted inventory wholesale – especially when you have a large quantity of rejected products, your supplier may prefer selling them on the grey market to disposing of them properly.

- Factory staff steal and sell unwanted goods – it can be relatively easy for a few units to go missing unnoticed, especially when those are units you don’t want the factory shipping to you anyway. Factory workers may see this as an opportunity to turn this waste into cash.

- Destruction/disposal staff steal and sell unwanted goods – in the same way factory workers might quietly take defective products for their own use or sale, workers hired to destroy and dispose of defective products might do the same.

At this point, you may be wondering: with as many ways for my goods to end up on the grey market, how can I know if I’m at risk when I’m halfway across the world?

How to check if your products are being sold on the grey market

It can be hard to know exactly where your products are at any given time, especially when your supplier is overseas. But there are a few ways you can investigate and keep track of your goods that will help you sleep better at night:

- Maintain transparency with clear record keeping – be mindful of your order quantities per SKU. As a general best practice, it helps to have an outside inspector visit the factory and check the goods before shipping. One of their main duties is to confirm unit quantities and production status.

- Search for your or similar products on popular ecommerce sites – sites like eBay, Craigslist, Amazon and Alibaba are often the first place where knockoffs or grey-market goods appear for sale.

- Be on the lookout for low prices – unauthorized distributors often sell grey market goods at a discount.

- Buy your own product occasionally from sellers – this gives you the chance to confirm lot numbers and account for your goods.

These are just a few easy ways to tell if your products are on the grey market. But given the lack of legal recourse available to you in the event you find your defective products on the grey market, you might’ve guessed by now that prevention is the best policy. And the best way to keep your defective products out of unauthorized distribution channels is usually total product destruction and disposal.

Of course, there are situations where product destruction would be a heavy-handed and unnecessary solution, provided alternative corrective action is possible. So before we examine how to approach product destruction, let’s look at some possible alternatives that might suffice.

⇑ Back to Top

Chapter 2: Alternatives to Total Product Destruction

Wholesale product destruction is generally seen as a last resort for handling defective products. Indeed, there are a few other far less destructive defect management measures that can both save time and salvage your inventory. Let’s look at three of the most popular alternatives.

Reworking or repairing defective products

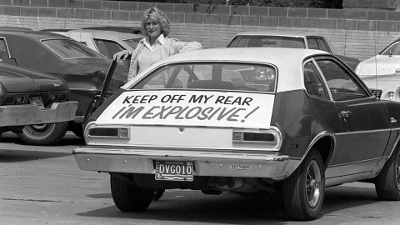

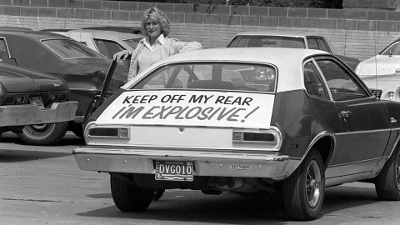

There are many cases where quality defects and other product issues can be resolved relatively easily through product rework or repairs. For example, take the case of the Ford Pinto, a subcompact car that sold from 1970 to 1980. A defect in the Pinto’s fuel system posed a serious risk of injury and death to occupants in the event of a rear-end collision.  Ford came under intense scrutiny following the release of an internal memo showing a cost-benefit analysis. The analysis led Ford to forgo repairing the cars for $11 each because such repairs were more costly than the value the company placed on the expected loss of human lives from crashes.

Ford came under intense scrutiny following the release of an internal memo showing a cost-benefit analysis. The analysis led Ford to forgo repairing the cars for $11 each because such repairs were more costly than the value the company placed on the expected loss of human lives from crashes.

Ford later recalled and discontinued the Pinto. But the controversy represents a high-profile case where a recall could have been prevented relatively easily without the need to scrap an entire batch or product line.

Product rework or repairs can be a practical solution to addressing a multitude of different quality issues. In fact, if you discover issues before the goods leave the factory, such as during pre-shipment inspection, you can often ask your supplier to conduct rework or repairs at little or no extra cost to you.

But there is one main caveat to product rework: the risk of introducing new defects to your goods. Each additional production and packaging process represents another opportunity for introducing a new defect or other quality problem to your product. When you ask your supplier to sand a rough surface on an item of furniture, for example, you risk workers over sanding the area or scratching, chipping or otherwise damaging the surface of the product during handling.

Always consider the severity of any defects you hope to remedy with rework or repairs and the potential risks of causing new defects in the process.

Asking your supplier to replace defective products

When product rework or repair is infeasible or risky, or when you’re working with a strict deadline that doesn’t permit it, asking your supplier to replace the defective products may be your best option.

As most importers will attest, it’s nearly impossible to mass manufacture a product without finding some defects in the batch, especially when manufacturing consumer goods in a developing country. That’s why experienced importers typically approach manufacturing with tolerances in mind for various types of product defects, often expressed as acceptable quality limits (AQL).

They establish these tolerances with their supplier well ahead of time so production and quality control staff have a clear understanding of expectations before manufacturing begins. Then, if inspection of the finished goods later reveals defective units in excess of the tolerances agreed upon with their supplier initially, it’s far more likely the supplier will be willing to replace defective products to make up for the difference.

Replacing defective units can solve your immediate problem of needing to ship a minimum quantity of conforming goods. But a longer-term defect management solution would be to audit the processes responsible for the defects and address them at the source.

Another issue entirely is if replacement goods don’t live up to your quality standards either. If you haven’t discussed product warranties and how to provide quality replacement goods, your manufacturer might supply you with substandard units because they never planned for replacements. Researching quality fade, product failure rates for your product category and how to address product warranties can help you avoid getting substandard replacement goods.

Charging back your supplier for defective products

Similar to asking your supplier to replace defective or substandard goods, charging your supplier back for them is another solution that can work for some importers. But supplier chargebacks do have a couple of distinct disadvantages.

Firstly, while chargebacks can help you recoup your manufacturing costs, they typically don’t solve the immediate problem of meeting customer demands. You’ll most likely end up apologizing to your customers for under fulfillment. And they may or may not be satisfied with a refund to offset the shortage of goods they receive.

Secondly, getting your supplier to accept a chargeback can be difficult. You’ll often need to leverage:

- A high order volume or frequency

- An established, long-term supplier relationship

- A formal, local manufacturing contract; or

- All of the above

Most factory owners will, understandably, be less than pleased to refund part or all of a purchase order to a customer. And in many cases when the customer in question is new, has a small order quantity or is otherwise insignificant relative to other larger or more-established customers, the factory owner has little incentive to cooperate with refunding payment for defective goods.

When importers believe they have a legally binding contract in place that addresses defective products, they may be caught off guard when local law doesn’t recognize the agreement. Many importers manufacturing in China, in particular, encounter this problem because they mistakenly think that judgements in the U.S. or another foreign country will be enforced in China.

When importers believe they have a legally binding contract in place that addresses defective products, they may be caught off guard when local law doesn’t recognize the agreement. Many importers manufacturing in China, in particular, encounter this problem because they mistakenly think that judgements in the U.S. or another foreign country will be enforced in China.

The best, and perhaps only, way to hold your overseas suppliers legally accountable for honoring an agreement is to have that agreement drafted in the supplier’s country by a local lawyer. And even then, taking legal action against a supplier in a foreign jurisdiction for breach of contract can be both challenging and expensive.

If you expect your supplier to pay you back for goods that don’t meet your standards, be sure to discuss this with them before placing the order. Even reaching an informal agreement before mass production can help you to better hold your supplier accountable in the event of unacceptable product issues.

Any combination of these options for dealing with defective products may be best for you, depending on the circumstances. But when issues that can’t be reworked or repaired affect the majority of your shipment you may want to explore available methods for certified product destruction and disposal.

⇑ Back to Top

Chapter 3: What are the Best Methods for Certified Product Destruction?

Some importers make the mistake of simply asking their supplier to dispose of their products. They think the factory manager will arrange to dump their unwanted goods into a nearby landfill and leave it at that, feeling safe in the assumption that they’re protected.

But unfortunately, the reality is quite different. The manager at your supplier’s factory likely has a strong motive not to discard your rejected products, despite your expectations for doing so.

According to Mike Rozembajgier, a previous vice president of a firm that helps companies handle product recalls, most manufacturers choose to simply throw away or incinerate defective goods. But the actual method you might use for your product will likely vary depending on your product. You’ll want to consider the following factors regarding the method when approaching product destruction:

- Is the destruction method effective? Destruction is only effective if it ensures your products can’t be sold.

- Is the destruction method efficient? Many different methods can work for your particular product. But some will take longer and be more costly than others. It’s in both your and your supplier’s best interest to choose a method that is relatively efficient.

- How can you certify the destruction process? If you can’t personally be on-site where destruction will occur, it’s best to send a trusted agent to oversee and certify that destruction is effective and complete.

Let’s look at a few actual examples of products importers chose to destroy.

1. Exercise gloves destroyed by shredding

On one occasion, a Chinese supplier to an exercise apparel company had a change in top management at the factory. The change in management led to a drop in product quality of subsequent orders and an increase in lead time at the factory over a period of time.

This problem led to an order of about 200,000 pairs of fitness gloves being unsellable. The quality problem was identified during a pre-shipment inspection. After some negotiation, the importer decided to destroy the gloves on-site. Over the course of five days, third-party inspection staff observed the gloves being fed, carton by carton, into an industrial shredding machine by a conveyor belt.

This problem led to an order of about 200,000 pairs of fitness gloves being unsellable. The quality problem was identified during a pre-shipment inspection. After some negotiation, the importer decided to destroy the gloves on-site. Over the course of five days, third-party inspection staff observed the gloves being fed, carton by carton, into an industrial shredding machine by a conveyor belt.

2. Fabric cushion cases cut with scissors

An importer of fabric cushion cases discovered that a significant portion of their order was defective due to shoddy, uneven stitching and misshaped patterns.

There were some acceptable pieces in the order. So a third-party inspector was brought in to sort the passable cushion cases from the defective ones and to witness the destruction of the latter. Factory staff then destroyed the defective cushion cases by cutting them up with scissors into four pieces each.

3. Defective earbuds crushed by a roller

Another example of product destruction comes from an importer of 30,000 pairs of promotional earbuds. These were branded earbuds with printed cartoon pictures. A product inspection near the end of production revealed major quality issues.  Namely, the cartoon characters were poorly printed and the earbuds’ wiring was falling apart.

Namely, the cartoon characters were poorly printed and the earbuds’ wiring was falling apart.

The importer decided to have the goods destroyed because they were defective beyond repair. After some discussion with factory management, they chose to crush the earbuds with a road roller. Independent inspection staff observed the roller drive over the earbuds several times. A truck then transported the destroyed earbuds for disposal.

In all three cases of certified product destruction above:

- The importer communicated their desire to have the goods destroyed to their supplier.

- The importer consulted an independent QC provider.

- The three parties discussed appropriate methods of destroying the goods and agreed to one that was both effective and efficient for the product at hand.

- And a local inspector from the QC provider observed the destruction process on-site and issued a report and certificate to the importer verifying the destruction method and the quantities destroyed.

Who pays for total product destruction services?

Importers considering total product destruction services sometimes wonder who will cover the various costs involved, such as rent for the necessary equipment, wages paid to workers that will handle or transport the goods and costs for hiring a trusted agent or inspector to observe and report on the destruction. Should you be responsible for these costs or should your supplier be?

The simplest answer is it depends. If your goods are defective because you neglected to provide a key requirement or product specification to your supplier before production, perhaps you’re responsible. If your supplier made an error when manufacturing the goods that rendered them unsellable, despite confirming their understanding of your requirements beforehand, it may make sense for them to pay for destruction.

But the most likely factor determining who pays for destruction isn’t usually what makes sense at the time. Rather, whatever understanding you reached with your supplier before placing the order will largely determine this. Just as with chargebacks and other penalties you may expect your supplier to pay when there’s a problem with the finished goods, expectations for who will be accountable to pay for product destruction services should be set up front.

⇑ Back to Top

Conclusion

No rational importer wants to destroy a large quantity of goods they’ve invested time and money into manufacturing abroad. And often alternatives, such as product rework or replacement, can solve your problem while salvaging your products.

But there are times when total product destruction is the best option for dealing with defective products. When you allow your supplier to handle a rejected order of unsellable goods as they see fit, you may be putting your brand’s reputation and intellectual property at risk. And if you rejected products due to serious safety concerns, you may even be putting consumers in danger by leaving them with your supplier to address.

So keep destruction in mind as a protective measure. And remember that there are right and wrong approaches that will depend on your product and unique situation. Advising your supplier of how you’d like your products handled is just one important part of the process. Enlisting the help of a trusted agent to see that your wishes are actually carried out is another part entirely.

More product destruction resources

Are you in need of total product destruction services? Click the link below to download InTouch's service guide and find out how we can help protect your brand!

This seems to be what happened to Antsy Labs’ widely popular Fidget Cube.

This seems to be what happened to Antsy Labs’ widely popular Fidget Cube.

When importers believe they have a legally binding contract in place that addresses defective products, they may be caught off guard when local law doesn’t recognize the agreement. Many importers manufacturing in China, in particular, encounter this problem because they mistakenly think that

When importers believe they have a legally binding contract in place that addresses defective products, they may be caught off guard when local law doesn’t recognize the agreement. Many importers manufacturing in China, in particular, encounter this problem because they mistakenly think that

Namely, the cartoon characters were poorly printed and the earbuds’ wiring was falling apart.

Namely, the cartoon characters were poorly printed and the earbuds’ wiring was falling apart.