Have you ever ignored the “wash with like colors” label on your clothes only to have your red shirt stain all your white towels? Or have you ever hung a beach towel out to dry only to find its bright blue color faded to a baby blue by the next morning?

Have you ever ignored the “wash with like colors” label on your clothes only to have your red shirt stain all your white towels? Or have you ever hung a beach towel out to dry only to find its bright blue color faded to a baby blue by the next morning?

Consumers don’t like their textiles to change colors or bleed during washing, under the sun or anywhere else. But how can you ensure the textiles you manufacture keep their color over time?

The best way to ensure your fabric’s color can withstand regular use is to test it in different conditions before shipment. Color fastness testing in a third-party laboratory can help you ensure your fabric’s colors stay fresh and vibrant after many uses.

Many international color fastness testing standards exist to help importers evaluate the durability of their dyed fabrics. A laboratory can help you choose which tests are most important for your fabric type and target market.

We’ll help you get started by introducing five of the most common color fastness tests in this article.

Why textile importers should conduct color fastness testing

Color fastness is the resistance of a fabric to change in its color characteristics or to transfer its colorant(s) to adjacent materials. Color fastness issues can be caused by:

- Fiber type: Fibers must be compatible with their chosen dye. A cellulosic fiber and a vat dye together have good resistance to fading, for instance, while polyesters perform well with substantive dyes.

- Dye type: The larger the dye molecule is, the easier it will attach to the fiber. Some dyes are also water soluble, while other are insoluble.

Poor color fastness can cause fabric shade variation or  the staining of other products. Any number of activities associated with regular use can reveal these issues, including:

the staining of other products. Any number of activities associated with regular use can reveal these issues, including:

- Washing

- Rubbing

- Exercising

- Sun exposure

- Dry cleaning

- Bleaching

- Ironing

Unlike other types of fabric testing, such as flammability, there are no mandatory legal requirements for color fastness testing. But color fastness testing is essential to ensuring customer satisfaction with fabric products.

Color fastness issues will often prompt consumers to reject the product and return it or submit a claim. Worse still, the customer will lose confidence in your brand if they perceive poor performance and durability in your products.

QC inspectors can conduct some color fastness testing at a supplier’s facility before shipping, such as washing or crocking testing (related: 5 On-Site Product Tests for Garment Inspection).

But a professional lab can test your fabric under many conditions that an inspector can’t replicate on site, such as elevated humidity levels, continuous sunlight and heavy perspiration.

Asking your inspector or supplier to send samples of your textiles to a laboratory for further testing can offer added assurance of your product’s color resilience.

How professional laboratories evaluate color fastness

Professional laboratories typically conduct product testing according to international standards for your target market. Since color fastness standards are not a legal requirement, importers can typically test their products to whatever  standard they feel is most appropriate for their target market.

standard they feel is most appropriate for their target market.

The American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) color fastness standards are the most commonly used in the U.S. and EU, respectively.

For most ISO and AATCC color fastness tests, the fabric specimen’s color after testing is compared to a “Grey Scale for Color Change” and a “Grey Scale for Staining”.

The Grey Scale for Color Change rates the color fading of the specimen on a scale from 1 (greatest change) to 5 (no change). The Grey Scale for Staining rates the staining of an undyed material tested with the specimen from 1 (greatest color transfer) to 5 (no color transfer).

1. Color fastness to detergent washing test

Color fastness during washing is one of textile importers’ main concerns. A textile item must withstand repeated washing throughout its lifecycle without losing its color properties or staining other articles its washed with.

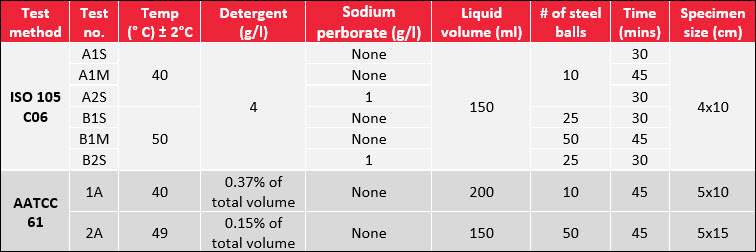

Detergent washing testing determines the resistance of textile colors to domestic or commercial laundering procedures. The two main standards for detergent washing are ISO 105 C06 and AATCC 61.

Aim for a color change rating of 4 and a color staining rating of 3 to 5 for detergent washing.

ISO 105 C06

There are 16 different ISO 105 C06 test procedures, ranging from A1S to E2S.

The “S” in the ISO 105 C06 test number refers to a single commercial or domestic laundering. The “M” refers to multiple washes, or approximately five domestic or commercial launderings. The “2” test procedures include a peroxide-based bleach, sodium perborate (NaH2BO4), in the washing water.

The “A” and “B” ISO 105 C06 test methods are most common, as they test fabrics at 40°C and 50°C, respectively. The “C”, “D” and “E” methods test fabrics at higher temperatures with different bleaches and softeners.

AATCC 61

There are five test procedures under AATCC 61, but the most common test procedures are 1A and 2A. 1A applies to hand washing at 40°C, while 2A applies to machine washing at 49°C.

The lesser used 3A procedure tests fabrics at 71°C, while 4A and 5A add a chlorine-based bleach, sodium hypochlorite, to the washing water. All AATCC 61 test procedures mimic five domestic or commercial launderings.

For both the EU and U.S. standards, the lab washes the fabrics with stainless steel balls to mimic abrasion. The number of balls, the amount of detergent and the washing time vary based on the test method.

2. Color fastness to crocking test (wet and dry rubbing)

“Crocking” is an industry term referring to a transfer of a colorant through rubbing. The crocking test determines the resistance of textile colors to rubbing off and staining other materials. A fabric with poor color fastness could rub colorants off on consumers, furniture, other textiles or miscellaneous items.

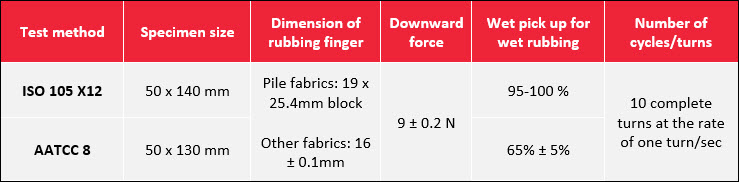

ISO 105 X12 and AATCC 8 are the primarily standards for measuring color fastness to crocking. The standards are partly equivalent and largely similar in their test methods.

ISO 105 X12 and AATCC 8 procedures

In both the ISO 105 X12 and AATCC 8 test methods, the test samples are rubbed with a dry rubbing cloth and then a wet cloth.

The ISO 105 X12 and AATCC 8 test methods both use a machine known as a “crockmeter” to rub the fabric. The crockmeter has a “rubbing finger” which the lab technician rubs across the fabric by turning a mechanical lever. The crockmeter applies a stronger force for a longer period than an inspector can manually apply when performing inspection at the supplier’s facility.

The rubbing fingers vary in size for pile fabrics and other textiles. The rubbing direction can also vary based on the type and design of the fabric. But the crockmeter typically rubs the fabric in the warp and weft directions separately. The direction is particularly important for striped or pattern fabrics for which results can vary.

The staining of the rubbing cloth is then assessed using the Grey Scale for Staining. Many textile importers will accept a grade 4 rating for dry rubbing and grade 3 rating for wet. Color fastness to wet rubbing is typically lower than for dry rubbing for most fabrics.

ISO 105 X12 and AATCC 8 vary mostly in the amount of water used to wet the cloth rubbed on the test specimen. The amount of water is calculated as “wet pick up”, or the amount of fluid by percent weight picked up by the fabric. ISO 105 X12 requires the cloth be wetter than that following the AATCC 8 standard.

3. Color fastness to light test

3. Color fastness to light test

The color fastness to light test determines the effect of natural sunlight on textile colors.

All textile colorants are susceptible to some fading in sunlight, as colorants by nature absorb certain wavelengths. But you don’t want your colored fabric to fade too quickly over the course of its life.

Color fastness to light testing might be particularly important to importers of clothing worn predominately outdoors. But even retail display lighting can cause fading. So all textile importers should consider this test for their products.

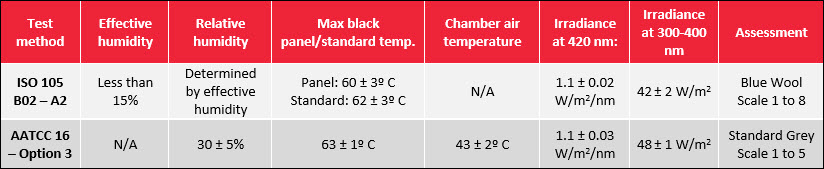

ISO 105 B02 and AATCC 16 are the most common international standards for color fastness to light. Both standards test fabrics under a Xenon Arc lamp that closely resembles natural sunlight. But the standards vary significantly in their assessment methods.

ISO 105 B02

ISO 105 B02 has four different exposure cycles with different humidity and temperature levels, including A1, A2, A3 and B. Many importers use A2 because it mimics extreme low humidity conditions.

ISO 105 B02 varies from AATCC 16 in that a blue wool reference material with a known reaction to light is simultaneously exposed to light during the test. The fading of the test sample is then rated in comparison to the fading of the blue wool reference. The Blue Wool Scale ranges from 1 (very low color fastness to light) to 8 (very high color fastness to light).

In ISO 105 B02 A2, the lamp can also have either a black panel (uninsulated) or black standard (insulated) sensor to control the temperature.

AATCC 16

AATCC 16 includes five different testing options. Option 3 is the most commonly used because it simulates extreme low humidity conditions and is most equivalent to the ISO 105 BO2 A2 cycle.

The Option 3 procedure subjects the fabric to continuous light, while some other AATCC 16 options subject the fabric to alternating light and dark conditions. Option 3 uses a Xenon lamp with a black panel sensor, while Option 4 and 5 use black standard sensors.

AATCC 16 differs from ISO 105 B02 in that light exposure in the former case is measured using a specialized unit of irradiance known as “AATCC Fading Unit” (AFU). Most apparel units are exposed to 20 AFU and rarely need to be exposed to more than 40 AFU. Upholstery should be exposed to 40 AFU and draperies to 60 AFU. The greatest exposure time is 80 hours on this scale.

The color change of the fabric is measured using the Grey Scale for Color Change, as in other AATCC color fastness test standards. Importers will typically accept a grade 4 rating for this test.

4. Color fastness to perspiration test

4. Color fastness to perspiration test

The color fastness to perspiration test determines the resistance of textile colors to human perspiration.

Fabric dyes and human perspiration can often react and cause color fading in clothing items. A color fastness test for perspiration are particularly relevant for sports apparel and swimwear, which will most likely be exposed to heavy perspiration during use.

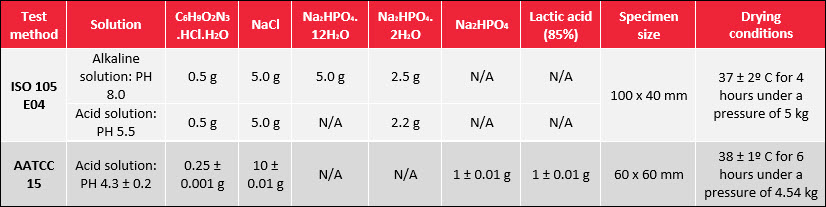

ISO 105 E04 and AATCC 15 are the two main standards for perspiration testing. For this test, the lab attaches a strip of multifiber fabric to the test specimen to measure staining. This multifiber fabric has swatches of different kinds of fibers, such as nylon, cotton, acetate, polyester, wool and acrylic fabrics.

The lab then compares the staining of the multifiber fabric to the Grey Scale for Staining, with a desired grade 3 rating. The lab compares the color of the test specimen with the Grey Scale for Color Change, with a desired grade 4 rating.

ISO 105 E04

During this test, the lab soaks the fabric in a simulated perspiration solution for 30 minutes under a fixed pressure and then dries it slowly at an elevated temperature.

ISO 105 E04 tests for color fastness to both acidic and alkaline perspiration. Human sweat is typically acidic, though it can become alkaline in higher temperatures or when bacteria are present.

AATCC 15

AATCC 15 only tests color fastness to acidic perspiration. The AATCC previously included alkaline test methods in the standard but removed it in 1974, as they didn’t believe it reflected normal end usage.

The drying time, pressure and temperature also vary between ISO 105 E04 and AATCC 15. AATCC 15 requires the fabric to be heated for longer at a slightly higher temperature than ISO 105 E04.

5. Color fastness to water test

Color fastness to water determines the resistance of textile colors to immersion in water.

You might think this test sounds like the washing test. But color fastness to water testing is specifically used to measure the migration of color to another fabric when wet and in close contact. The washing test also typically uses a basic PH solution due to the addition of detergent, while this test is conducted at neutral PH levels.

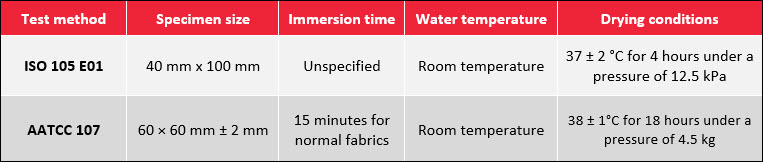

ISO 105 E01 and AATCC 107 are the most common standards for color fastness tests to water. The standards are technically equivalent, but the testing methods vary slightly between them.

ISO 105 E01 and AATCC 107 procedures

For this test, the lab technician attaches a strip of multifiber fabric specimen to measure staining, as with the perspiration test. The test specimen and multifiber fabric are immersed together in water under specific conditions of temperature and time.

After soaking, the fabric is then placed between glass or plastic plates and dried under specified time, pressure and temperature conditions.

The multifiber fabric is then compared to the Grey Scale for Staining and the test specimen is compared to the Grey Scale for Color Change. Many importers will accept a grade 3 rating for staining and a grade 4 for color change.

ISO 105 E01 and AATCC 107 vary most in the heating time of the test specimen after immersion. AATCC 107 requires the specimen to be heated for longer than ISO 105 E01.

Conclusion

Some color fastness tests might be more important to you than others, depending on the design and intended use of your textile products. Other standards also exist for color fastness to sea water, chlorinated water, hot pressing and other unique conditions.

Color fastness issues aren’t usually noticeable until after sale. But textile fading and staining can cause serious headaches for your business when customers later discover these issues (related: 3 Ways to Manage Garment Quality Control).

So if color resilience is important to your customers, don’t take unnecessary risks. Hire a professional laboratory to test your fabrics and ensure optimum color fastness levels before your next shipment.

Your fabrics will retain their vivid and vibrant colors for long after the initial sale, keeping your customers satisfied and coming back for more.

Contact AQF today to learn about how can our quality experts help you retain the color of your garment products and enhance quality.